· Here are some model A Level essays, written for the new OCR specification. The essays are all out of 40 marks (16 AO1 and 24 Ao2) and written with A Level notes, using my standard A Level plan (below), in 4o minutes the amount of time you will have in the final examination. Obviously enough, these answers represent one possible approach and are only Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins · How to structure AQA A-level History Essays. For AQA History, at both AS and A level, you need to know how to write two types of essay – a block essay and a point-by-point essay. To be able to structure AQA history essays you’ll need to know these essay styles and where to use them The basic framework for an A Level essay is standard: Introduction. Argument 1. Argument 2. Conclusion. However, certain techniques used within this structure are what can help present your knowledge in the most effective way for reaching the higher marks: What to include within each of these 4 sections

Writing A Level Essays | Logos

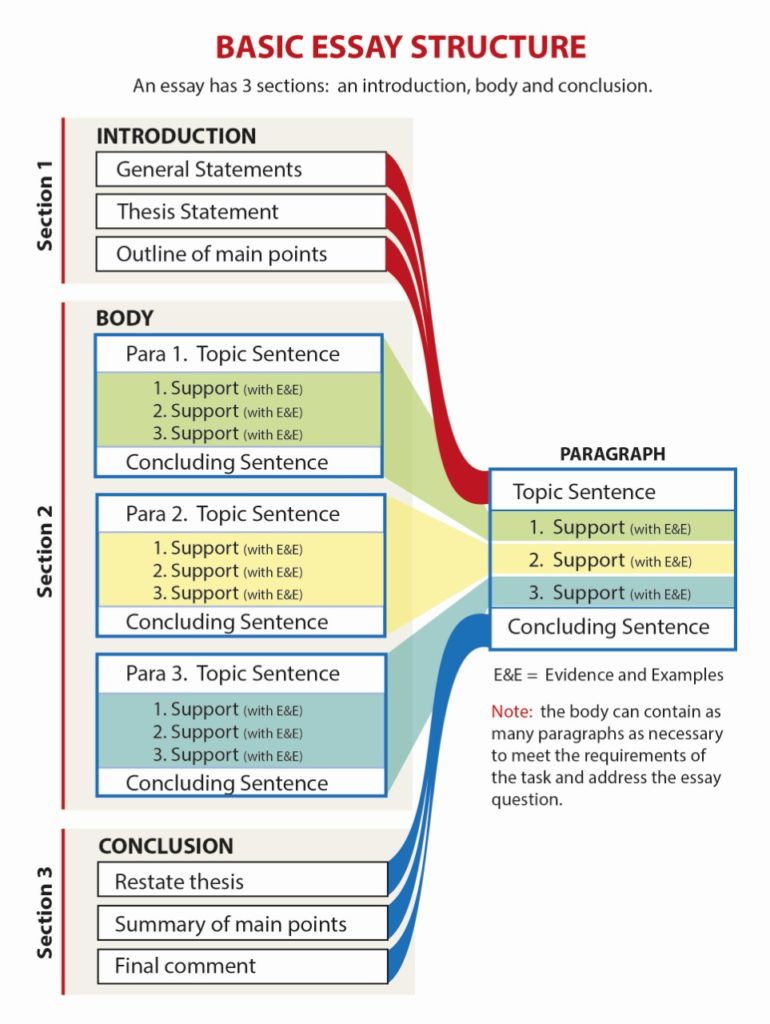

Writing an academic essay means fashioning a coherent set of ideas into an argument. Because essays are essentially linear—they offer one idea at a time—they must present their ideas in the order that makes most sense to a reader, a level essay structure.

Successfully structuring an essay means attending to a reader's logic. The focus of such an essay predicts its structure. It dictates the information readers need to know and the order in which they need to receive it.

Thus your essay's structure is necessarily unique to the main claim you're making. Although there are guidelines for constructing certain classic essay types e. Answering Questions: The Parts of an Essay. A typical essay contains many different kinds of information, often located in specialized parts or sections. Even short essays perform several different operations: introducing the argument, analyzing data, raising counterarguments, concluding.

Introductions and conclusions a level essay structure fixed places, but other parts don't. Counterargument, for example, may appear within a paragraph, as a free-standing section, as part of the beginning, or a level essay structure the ending.

Background material historical context or biographical information, a summary of relevant theory or criticism, the definition of a key term often appears at the beginning of the essay, between the introduction and the first analytical section, but might also appear near the beginning of the specific section to which it's relevant. It's helpful to think of the different essay sections as answering a series of questions your reader might ask when encountering your thesis.

Readers should have questions. If they don't, your thesis is most likely simply an observation of fact, not an arguable claim. To answer the question you must examine your evidence, thus demonstrating the truth of your claim.

This "what" or "demonstration" section comes early in the essay, often directly after the introduction. Since you're essentially reporting what you've observed, this is the part you might have most to say about when you first start writing. But be forewarned: it shouldn't take up much more than a third often much less of your finished essay. If it does, the essay will lack balance and may read as mere summary or description.

The corresponding question is "how": A level essay structure does the thesis stand up a level essay structure the challenge of a counterargument? How does the introduction of new material—a new way of looking at the evidence, another set of sources—affect the claims you're making?

Typically, an essay will include at least one "how" section. Call it "complication" since you're responding to a reader's complicating questions. This section usually comes after the "what," but keep in mind that an essay may complicate its argument several times depending on its length, and that counterargument alone may appear just about anywhere in an essay. This question addresses the larger implications of your thesis. It allows your readers to understand your essay within a larger context.

In answering "why", your essay explains its own significance. Although you might gesture at this question in your introduction, the fullest answer to it properly belongs at your essay's end.

If you leave it out, your readers will experience your essay as unfinished—or, worse, as pointless or insular. Mapping an Essay. Structuring your essay according to a reader's logic means examining your thesis and anticipating what a reader needs to know, and in what sequence, a level essay structure, in order to grasp and be convinced by your argument as it unfolds.

The easiest way to do this is to map the essay's ideas via a written narrative. Such an account will give you a preliminary record of your ideas, and will allow you to remind yourself at every turn of the reader's needs in understanding your idea. Essay maps ask you to predict where your reader will expect background information, counterargument, close analysis of a primary source, or a turn to secondary source material, a level essay structure. Essay maps are not concerned with paragraphs so much as with sections of an essay.

They anticipate the major argumentative moves you expect your essay to make. Try making your map like this:. Your map should naturally take you through some preliminary answers to the basic questions of what, how, and why. It is not a contract, though—the order in which the ideas appear is not a rigid one.

Essay maps are flexible; they evolve with your ideas. Signs of Trouble. A common structural flaw in college essays is the "walk-through" also labeled "summary" or "description". Walk-through essays follow the structure of their sources rather than establishing their own.

Such essays generally have a descriptive thesis rather than an argumentative one. Be wary of paragraph openers that lead off with "time" words "first," "next," "after," "then" or "listing" words "also," "another," "in addition".

Although they don't always signal trouble, these paragraph openers often indicate that an essay's thesis and structure need work: they suggest that the essay simply reproduces the chronology of the source text in the case of time words: first this happens, then that, and afterwards another thing. or simply lists example after example "In addition, the use a level essay structure color indicates another way that the painting differentiates between good and evil".

CopyrightElizabeth Abrams, for the Writing Center at Harvard University. Skip to main content. Main A level essay structure Utility Menu Search. Harvard College Writing Program HARVARD, a level essay structure.

FAQ Schedule an appointment Writing Resources English Grammar and Language Tutor Departmental Writing Fellows Writing Resources Writing Advice: The Barker Underground Blog Contact Us. Answering Questions: The Parts of an Essay A typical essay contains many different kinds of information, a level essay structure, often located in specialized parts or sections.

Mapping an Essay Structuring your essay according to a reader's logic means examining your thesis and anticipating what a reader needs to know, and in what sequence, in order to grasp and be convinced by your argument as it unfolds. Try making your map like this: State your thesis in a sentence or two, then write another sentence saying why it's important to make that claim. Indicate, in other words, what a reader a level essay structure learn by exploring the claim with you.

Here you're anticipating your answer to the "why" question that you'll eventually flesh out in your conclusion. Begin your next sentence like this: "To be convinced by my claim, the first thing a reader needs to know is. This will start you off on answering the "what" question. Alternately, you may find that the first thing your reader needs to know is some background information. Begin each a level essay structure the following sentences like this: "The next thing my reader needs to know is.

Continue until you've mapped out your essay. Signs of Trouble A common structural flaw in college essays is the "walk-through" also labeled "summary" or "description".

Writing Resources Strategies for Essay Writing How to Read an Assignment Moving from Assignment to Topic How to Do a Close Reading Overview of the Academic Essay Essay Structure Developing A Thesis Beginning the Academic Essay Outlining Counterargument Summary Topic Sentences and Signposting Transitioning: Beware of Velcro How to Write a Comparative Analysis Ending the Essay: Conclusions Revising the Draft Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines. Quick Links Schedule an Appointment Drop-in Hours English Grammar and Language Tutor Departmental Writing Fellows Harvard Guide to Using Sources Follow HCWritingCenter.

Copyright © The President and Fellows of Harvard College Accessibility Digital Accessibility Report Copyright Infringement.

How to Write an Essay: 4 Minute Step-by-step Guide - Scribbr ��

, time: 4:21How to structure a history essay a level

21 hours ago · Essay on a hot summer day for class 3 essay level structure a Rs. Best way to close an essay essay about career goals in life an essay on children's literature: essay on kindness cannot be quarantined utility in a fallible tool a · This type of structure applies to “how far” questions as well. So, here we go: Like I said in my previous post, the introduction can be argued to be the most important aspect of an essay (to what extent do you agree that the introduction of an essay is the most important part of an essay. ��) WARNING: Long post �� Introduction:Estimated Reading Time: 4 mins · Here are some model A Level essays, written for the new OCR specification. The essays are all out of 40 marks (16 AO1 and 24 Ao2) and written with A Level notes, using my standard A Level plan (below), in 4o minutes the amount of time you will have in the final examination. Obviously enough, these answers represent one possible approach and are only Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins

No comments:

Post a Comment